What makes a hero?

How do you define an heroic act? Does it require laying it all on the line at just the right moment, risking or even giving one’s life for another?

How do you define an heroic act? Does it require laying it all on the line at just the right moment, risking or even giving one’s life for another? Standing up to the mob, taking a bullet, running into the fire? I think the day-to-day hero may have the more difficult task. The one who deals with the grind, the tedium, the stress, working relentlessly to make a difference and help someone, with no hope of recognition; these people should at the very least be included in the definition.

When I arrived at my job some 18 years ago, I was thrilled to work at a medical center that was truly at the leading edge. For example, many know of the depth of talent in our local cardiology group, which is second to none. But less is known of our cancer center, which wasn’t even an accredited entity in 2000. But our breast cancer program has always been one of the most progressive anywhere. We were one of two centers in the United States (the other being Stanford) utilizing large format histology to better correlate disease with imaging, and we are still using it today. The multidisciplinary review of all breast cancer patients remains the benchmark for quality. Our treatment offerings across the board are state of the art, and we pass the ultimate test for any doctor: this is where I would send my family member or friend, this is where I would be treated.

But I got handed lung cancer. Ugh. When I started, well, let’s just say the program was a bit less organized than some others. Granted, this is not a unique issue, because lung cancer is a very different animal. So we set about trying to rethink the whole shebang.

We were already presenting our patients in a similar multidisciplinary format with representatives from all of the different treatment modalities, but it was typically not what you would call an “uplifting” conference. Breast cancer, with a proven method of screening and a variety of effective treatment plans, is fortunately a battle won more often than not. Lung cancer… not so much.

Many patients present at high stage and treatment options are much more limited. Adding this to the that fact that cutting out pieces of the organ you use to breathe – especially in a patient who has smoked for much of their life – carries a bit of risk, and you may begin to appreciate the difficulties of warding off feelings of futility.

But nothing was more frustrating than looking at a CT of a big, inoperable lung cancer and then being shown a study from two or three years prior where the beginnings of the mass could be seen (only much smaller), but for one reason or another, wasn’t followed up. If only!

And this happened. A lot more than I care to admit.

So we decided to do something about it. And this began the creation of a program that was going to forever change my view of what was possible, of the potential impact of doing things just a little bit differently, and also change my definition of a hero. We called it our “safety net,” because it protected us from allowing people to slip through the cracks. But it wasn’t really a net, it was a person, and her name is Sue.

To catch people before they slip away means you have to find them in the first place. And that was what Sue did. She read every report from every X-ray or lung CT from every single patient in our system to see if there was an abnormality. And if the report said that something looked funny and suggested that the study be repeated in follow-up, she made a note. She would document the recommendation, and then enter it into a calendar and wait. She would wait to see if the patient got the repeat study. And if not, she would hunt them down. She would find their physician or whoever was responsible, going so far as to send certified letters to patients to be sure no one was left behind.

It’s worth noting that this was (and still is) an innovative position. We saw a need and figured out a way to address it; we didn’t have a consultant or another healthcare system to show us the way. The administration at Centra deserves credit for helping to realize our vision in a world where every dollar counts and authorizing some unorthodox plan that revolves around a service that you can’t bill for is a rare and risky adventure. It’s also not the kind of job that you can explain with ease at a cocktail party. “What is it you do again?”

“I am a safety net…”

In the movies, some heroes keep a count of the bad guys they take down. For Sue, we kept a record of the lives that she saved. Let me say that again so that it sinks in: we have a count of the number of lives that she saved, people who were going to go on oblivious that a deadly disease was slowly (or in some cases, not so slowly) growing inside them. I don’t remember the final count when she retired, but it was well into the 50s. Fifty-plus lives saved. That’s a fully-loaded Greyhound bus.

To my knowledge, Sue never wore a special costume, nor do I remember any parades in her honor. In fact, I am not sure a single patient understands the impact of what she did. For certain, some were annoyed at her intrusion. 8000+ hours a year, sitting at a desk, reading radiology reports. It’s not exactly the stuff Iron Man does for entertainment. It’s tedious, mundane work. But she saved people’s lives, and she didn’t need cutting edge science or some miraculous gadget, she just got it done.

Sue continued to work even when her husband developed cancer. She pushed on as he underwent a variety of treatments, with some successes, but ultimately unrelenting progression. Sue and Jim were one of those couples that had a connection few enjoy, and his death will always be a reminder to me that life just isn’t fair.

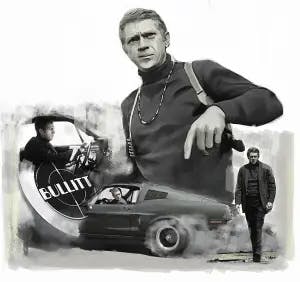

I only met Jim a couple of times, but that mattered little, because Jim was a car guy. I was particularly delighted by his Shelby GT500. If you are also a car guy, then I don’t have to explain. In case you’re not, here is the deal: It’s a mustang with 500 horsies and a stick shift. That’s a combo that was rare at the time, but is easily on the endangered species list today. I used tell Sue I was sure he wasn’t driving it enough, and I knew he wasn’t doing near enough donuts and burnouts (you just can’t do too many donuts and burnouts). I never actually saw the car, but for some reason I had it in my head the thing was white. That will become important…

If you are a car guy, you know about the exploits of Carroll Shelby. He was involved in the development of high performance cars – including the GT500 – right up until his death. He was always approachable, and the number of dashboards that he signed must be uncountable. And that also turns out to be somewhat important…

Because I accidently bought what I now like to think of as the spiritual successor to Jim’s GT500.

This winter, in a bit of a whim intended to allow me to blow off some steam during a difficult time, I decided to buy a fun car unlike anything I had owned before. I wanted a used something or another I could drive for a bit and sell for minimal loss, something that made a lot of noise. Something that did really, really good donuts and burnouts. (Because you can never do too many donuts and burnouts).

I was really curious about the Shelby GT350, but they are hard to find. Like a lot of collectable cars, people tend to leave them in their garage and periodically wipe them with a diaper. To make my plan work, I needed something that had been driven, both to bring the price down and to cover the slew of miles (and donuts and burnouts) that I intended to enjoy. When one popped up just an hour away, I jumped at the chance to have a go.

Fast forward, and a decidedly noisy and very red GT350 sits in the garage. I am going to admit I was a bit surprised when I found out that Jim’s had in fact been red as well. I would have sworn the thing was white… Coincidence? Perhaps. But I can honestly say I find it all but impossible to even look at the thing without being reminded of Jim and of the sacrifice that Sue gave to help so many.

And I like it that way. It is so easy to take things for granted, to allow frustration and annoyance and tedium to drag us to a stop, to fail to press on when the road becomes more than we care to endure. We all need reminders of what is possible with perseverance, with persistence, with unrelenting forward progress. Coincidence or not, I intend to fill my vision with the headlights of the inspirational, any way I can.

So I made my own dash plaque in hopes of having it signed. But it’s not Carroll Shelby’s scribble that I want, it’s Sue’s. And Sarah’s, and Amanda’s, and Carol’s, and many others, the ones who every day act the hero by showing up and getting it done, making a difference – saving lives – day after day, in rather mundane ways. And in an attempt to spread the inspiration around, each time I manage to add another name, I will pass on a bit about that particular hero, so their stories can be heard as well. Some of them are doing what they do because of Sue’s success and what we all learned from it, steady winds that began with the wing beats of a butterfly. I will never be able to recognize even a small fraction of those that deserve it, but if I can add even a little to what has been done, I will consider it a success.

And, of course, there will be many donuts and burnouts!

Jim’s GT500. Not a car for slick roads!

Mine lacks the stripes, but it’s plenty loud.

Dash plaque looking bare… thus far.

And in case you don’t get the plate…