Effective Transportation in Smaller Cities and Rural Areas

Over the past seven years, our team has worked to build a financially sustainable system that has proven to better meet the needs of the community. We did this by flipping the business model of public transit on its head.

Bullet Points:

- Fixed-route buses and on-demand systems are not effective in smaller cities and rural areas and are expensive to operate.

- Pre-scheduling rides assures minimal waste but is more challenging to implement.

- Customers will pay for service that meets their needs, but will not pay for substandard systems, so make sure what you do is effective.

- Effective public transit in smaller cities and rural areas is more about customer service than it is about technology.

- The lower the population density, the more important it is to be able to use every available resource, including those not traditionally under the public transit umbrella (volunteers, rideshare, non-emergent medical transport).

Our city – Lynchburg, VA – has a typical public transit system that is largely ineffective because of the relatively low population density. While everyone acknowledges this, little work has been done to try to improve the system beyond adjusting bus routes and stops. Meanwhile, people in the more rural surrounding counties have no public transit at all. Over the past seven years, our team has worked to build a financially sustainable system that has proven to better meet the needs of the community. We did this by flipping the business model of public transit on its head. In fact, approaching the problem from outside the existing public transit system has been fundamental to our success.

As an analogy, think of transportation as a sandwich shop. The goal of public transit is to be sure everyone has a sandwich, so the typical approach is to make as many sandwiches as possible at the lowest unit price in the hope that everyone will at least get something. The use of large sandwich machines (buses) allows high production at rock bottom prices. To evaluate how well this is working, the standard metric is how many sandwiches are eaten (utilization or ridership). While this approach works someplace like New York City, it has serious limitations when the population density drops.

First, counting the number of sandwiches that get eaten is not a good metric, because you can have a lot of satisfied customers and still have people starving in the streets. Even worse, if your sandwich isn’t very good, the only people eating it are literally the ones starving, so increased consumption may actually be an indicator of critical unmet needs.

Second, while the unit cost per sandwich may be low, if most of your product gets thrown away then you are generating tremendous waste. While each sandwich may be inexpensive, making 100 for every one that gets eaten is incredibly expensive. When you see a big bus that is largely empty, you are seeing mass quantities of sandwiches (and taxpayer money) being thrown away.

Finally, these cheap sandwiches are incredibly hard to sell, meaning the business never makes money. It’s normal for a public transit sandwich shop to bring in less than 10% of its operating costs from customers (fares). Reliance on continued investor support (government funding) is part and parcel to the business model.

From the very beginning, we imagined a different approach: instead of continuing to operate an ineffective, expensive system with substantial waste, why not build an attractive, effective system that is financially sustainable because the product is something people will pay for, and then leverage that system to better meet the needs of the community? Going back to our sandwich shop analogy, we decided to make the highest quality sandwiches using only the best ingredients at the lowest cost, but make every sandwich to order. This assures there is no waste, and while the sandwiches may each be more expensive, every sandwich gets eaten.

But the most radical shift is that we don’t give any sandwiches away – that’s right, there are no free sandwiches – and this is how we achieved financial sustainability in a market that has completely given up even trying to have a sustainable business. Even so, we are able meaningfully assist our most at-risk neighbors when the available options have proven completely ineffective.

How is this possible? Because while we don’t give any sandwiches away, we also don’t turn anyone away.

If you walk up to the public transportation sandwich counter you will be offered a sandwich, but if it won’t do, you are out of luck. If you walk up to our counter and ask for a sandwich, we will make sure what we put together is going to work for you. If you can’t pay for it, the reality is that you need more than just a sandwich.

In the world of social services, people’s needs are complex. Effective programs provide wrap-around support that is customized to the individual while requiring an appropriate level of accountability. Without this support, freebies get squandered. With it, basic transportation becomes a simple but effective tool for helping people get back on their feet. So, we don’t give out free sandwiches, but we do direct people to programs enabling them to overcome their barriers, and then those programs pay for the sandwiches.

Why? Because without an effective transportation solution, even the best wrap-around care programs will fail when people can’t get to where they need to go.

Our experience with Lynchburg Adult Drug Court offers a real-world example. A program of the Virginia Department of Health (VDH) overseen by the city court system, Adult Drug Court provides a comprehensive rehabilitation program for nonviolent offenders who meet certain requirements. It is an appointment-heavy program where participants have multiple supervisors and requirements including social work, peer support, and routine drug testing. Progression through the multiple stages is dependent on the success of the individual and the duration can exceed two years. However, graduates evolve into mentally strong, productive members of society as opposed to serving multiyear sentences and emerging as convicted felons.

At the request of the VDH, we began providing transportation support for participants at the end of 2022 at a contracted price matching our local taxicab fare: $2.80 a mile. Over the next nine months, we worked to meet any unmet needs of the 18 enrollees and ultimately billed the program $5071. The presiding judge passed on that he was sure at least four people would have failed out without our help. This would have resulted in their being returned to prison to serve out their full sentences at a cost to the city exceeding $500,000, meaning the city saw a 100x return on their $5000 investment while increasing the program success rate by 22%. We have had similar success serving the Department of Social Services with their Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) which is thrilled to pay us for transit services when it means they are much more effective.

The same approach works in most markets: schools can’t charge tuition if students can’t get to class, and businesses suffer if employees can’t get to work. The US healthcare system loses $100 billion annually on no-shows directly related to lack of transportation.

The most important component to achieving financial sustainability is only making sandwiches to order: pre-scheduled rides. This is how most paratransit systems operate, but the bulk of public transportation is either fixed route buses or various forms of curb-to-curb “on-demand” service. Like fixed route programs, on-demand service is very wasteful because it requires an excess of capacity so that someone is always ready to go. This is why you are always on hold with customer service, as no business can tolerate the expense of paying people to sit around “just in case.” It took us about a day and a half to understand the inefficiencies and unsustainability of on-demand transportation outside of a major metropolitan area.

A word of caution: pre-scheduled rides take a lot of work, as does addressing the needs of everyone that steps up to the counter. This is problematic for public transit systems, as they are not setup to do this type of work. Furthermore, flashy smartphone apps make many promises, but technology has to follow what we actually do, not the other way around. While we purpose-built our IT solution to help us manage our specific operational process and are proud that of its unique capabilities, the reality is that we are able to run our entire system with notepads and cell phones. In many ways, we are much more like – and work much closer with – the department of social services than we are a typical transit company. Big buses may be complicated but people are another animal entirely.

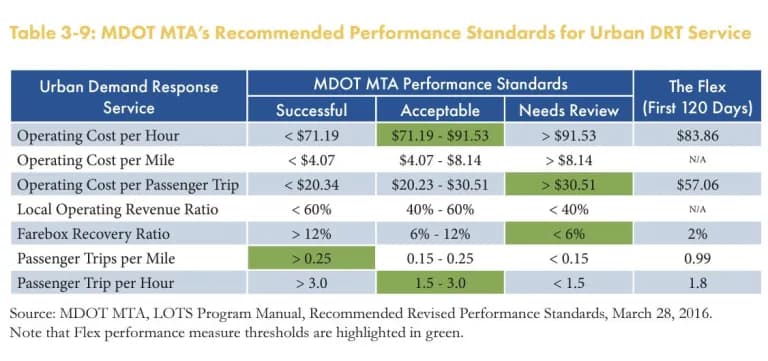

Tables 1-3 summarize financial and effectiveness data from a microtransit pilot program in Maryland (The Flex) as compared to similar datasets from our program titled ACTiN (Advanced Connected Transportation Network) from the beginning of Q4, 2023. While there are a lot of publications relating to microtransit, the vast majority are planning studies and there is very little true outcomes data to be found. Note the Maryland Department of Transportation’s Performance Standards in Table 1: Any Farebox Recovery Ratio of >12% – which means losing less than 88% of your money – is exceptional. The Flex recovered 2%. Our local bus company typically recovers about 6%. The microtransit program in Wilson, NC recovered 15% by charging $1.50 for rides that cost them $10.50 each. In October – the first month we were fully operational – we recovered 71%. In November: 108% – we brought in more than the cost of our operations, proving financial sustainability, and we continue to improve. By the way, please forgive the not-so-flashy charts, as my training is in medicine (and now transportation), not graphic design.

Table 1. Microtransit pilot program in Maryland (The Flex). Full Study Available Here | Backup Resource Link.

Table 2: ACTiN Data, October 2023.

Table 3: ACTiN Data, November 2023.

One component that helps us achieve this goal is our vehicle of choice: 2020 Model X Tesla, which has an operational cost of only $7 per hour. While buses easily cost over $100 an hour to operate, our target is $35 an hour, and of that expense, $28 goes to the driver, so even that goes back into the community. The lack of routine maintenance – there is no gas or oil or water – even extends to regenerative brakes which reduces brake pad and rotor wear significantly. While there is an argument that making the battery for an electric car negates the environmental benefit of not burning gas, reducing the use of other gas-powered cars evades this conundrum. Every community is different, but a busy driver working a 40-hour week can manage 3000 miles of transport a month, saving about 100 gallons of gas. Sharing the car with two drivers doubles these results.

The unintuitive but critical benefit of the Model X is actually the unique “falcon” doors. Public transportation has to meet strict requirements of the American Disabilities Act, but this actually leaves out people with limited mobility. If you have never helped a little old lady into a vehicle, you may not realize that even a minivan requires you to bend your knees and twist your body at the same time, significantly increasing the potential for a fall. This is not the case with the Model X, as standing someone at the threshold – even when they need assistance – is all you need to do to get them in safely. And in a society where liability is literally crippling, this is priceless.

All that being said, the reality of transportation – especially in rural areas – is that you have to be able to leverage every asset you have. This is where public transit (and pretty much every other organization in the US) falls down: no matter how effective the group or business or service, we are not good at handing our customers off to a competitor. Uber is never going to connect a rider to a taxi, and a taxi driver is never going to suggest you take a bus. This is another reason public transit needs to move away from utilization as its metric, and we have suggested shifting to ride completion rate. By focusing on enabling effective transportation as opposed to being the solution, public transit can adapt to the particular needs of the community to assure even the most complicated are being met. One of the tremendous powers of technology is being able to connect to people and enabling them to make their requests known, whereupon those in charge of managing the resources can help apply the most appropriate assets to get the job done.

In summary, transportation is a critical need in our society, a fundamental social determinant of health. Smaller cities and rural areas with lower population densities require a novel approach. By focusing on high quality, made-to-order services and minimizing waste, it is possible to build effective, financially sustainable systems that meet the needs of the community.